We are soon to upgrade digital signage across various museum sites, and my role has been to develop the various software mechanisms to gather and display the data for our prototypes. This is a brief post about how our prototype currently works. As a bit of background our legacy signage is based on flash which, although pretty and robust under certain circumstances, has several limitations making it no longer a valid option.

Use Cases

The software would be used by both museum staff wishing to publish events, and users who need to access information about the timings and locations of events. We also have other uses such as those wishing to display messages from sponsors or front of house staff.

Client Side

We chose to implement the signs in html/JavaScript as we already had a working model for doing this which could be adapted, and this would give us the most flexibility and control for future developments. I decided to use the Backbone JavaScript framework to organise the application because of the way it would allow different templates to be used for our different designs, and also because of the way the sign data could be defined and extracted from various sources before being published. This would allow us to be flexible about which systems we use to manage the data – some of these are still in specification, and so we have the option to change data sources quite easily in future. I also used the RequireJS plugin to manage the various other plugins and dependencies we may encounter during development. With this framework and application structure in place before work began it made building the application fairly straightforward and the modular design means we can troubleshoot effectively and adapt the designs easily in future.

Server Side

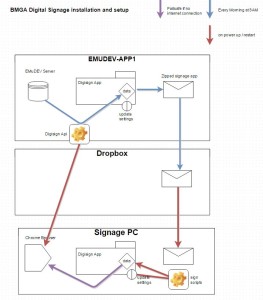

Because we already use the Events Module of the KE EMu Collections Management Software to manage the exhibition object and multimedia workflow, most of the data we wanted to publish to the signs already exists as event records – so we just needed a way to publish this straight from EMu. I developed a PHP API which returns a JSON list of events (title, description, dates, etc.) which can be accessed over Wi-Fi (hopefully!). To make the system more robust we also wanted the data and images to be held locally on the digital signs, so we also needed another way to send and store the data. I adapted the API to also save the events list to a file which could be stored locally on the signs to achieve this. Similarly for the multimedia this also needed to be saved locally in case of the Wi-Fi going down. To make life easier for staff we have commissioned a new tab in EMu specifically for digital signage – this brings together just the fields used to manage and display sign data, but it also means we can harness records that already exist in the system, in keeping with the ‘Create Once, Publish Everywhere’ ethos.

Additionally I also wanted to open up other options for source data to go to the signs, for staff that would not normally have access to our collections database, so I developed an API in Google application script to allow us to manage and publish data using a Google Docs spreadsheet, if needed.

Update Scripts

We needed a mechanism to transfer the application and its content over to the signs to be held locally. Our digital team were experimenting with Ubuntu for the sign OS so I built the data loader engine using Linux shell scripts. These scripts would download a zipped version of the software on power up, and unzip the files. This would also allow us to carry out upgrades to fix bugs and improve the design during testing. I decided to use a switch, contained in a settings file which could be used to control whether the whole sign application got updated, or just the images and text to be displayed. This way I can update signs individually for testing new releases. These settings would also control which mode the sign was in – so we can specify landscape vs portrait, or which museum building the sign was in so the branding could be adjusted. This settings file would have to live outside of the main application in order for us to use one app for all signs, and this process would need to be documented in the installation instructions.

So, the update scripts had logic for upgrading, or updating the sign data as well as some failsafe code in case of only a partial download or no internet connection. The various update scripts were controlled by a master script which would be set to run each time the sign was powered on, and this would also start Chrome in full screen kiosk mode with the various parameters for local file access and other bits.

Design

I used Chrome Dev tools to build the front end, working from a design supplied by our in house team. As the signs are pretty large and tall the Chrome screen emulator helped to get the proportions right. We decided not to go with a responsive design because tests had already showed problems with css media queries when connecting to digital screens, also there was not any use cases for small screens, and again our framework makes different designs easy to implement in the same app. The main issue so far with the designs is not knowing how many events records there will be on any one day, and so we don’t yet know if we will have to scroll / rotate the records, or if we will have trouble filling all the slots. For testing though I added some code to beef up the records in case there were not enough to fill each entry. The html was fairly simple – just a table and an image, but this was getting created from the source data using Underscore, a prerequisite of Backbone. The designs also specified images to fade in and out on rotation to represent the events, but not all events would have images, so I used a separate template and Backbone collection for images – this means the system won’t crash if not all events have images, (unlike our legacy flash software).

Further Information

Here’s a link to the latest release of the software on GitHub

Next steps

To work with team digital to refine and test the installation process, and see what our users think.

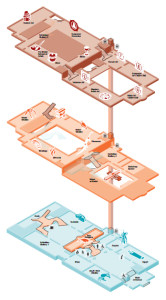

So… how best to implement triangulation in Unity? We take the perceived distance from all ‘visible’ iBeacons, and from that we work out the precise position of the device. After a few sprints of getting neck deep in advanced mathematics, we opted to use Unity’s built-in physics engine to do the heavy lifting for us… using Spring Joints from each iBeacon to automagically position the device on a virtual map, based on perceived distances from each iBeacon in range, allowing Unity to perform the complex maths for us.

So… how best to implement triangulation in Unity? We take the perceived distance from all ‘visible’ iBeacons, and from that we work out the precise position of the device. After a few sprints of getting neck deep in advanced mathematics, we opted to use Unity’s built-in physics engine to do the heavy lifting for us… using Spring Joints from each iBeacon to automagically position the device on a virtual map, based on perceived distances from each iBeacon in range, allowing Unity to perform the complex maths for us.

We knew that iBeacons work on distance, and so therefore the height at which we placed them would make a difference. But – perhaps naively -we didn’t expect this to cause much of an issue, so long as it was consistent. We didn’t take into consideration how powerfully the signals could penetrate through floors and ceilings… and certainly didn’t foresee issues caused by open atriums and balconies.

We knew that iBeacons work on distance, and so therefore the height at which we placed them would make a difference. But – perhaps naively -we didn’t expect this to cause much of an issue, so long as it was consistent. We didn’t take into consideration how powerfully the signals could penetrate through floors and ceilings… and certainly didn’t foresee issues caused by open atriums and balconies.